Tracking down mysterious swift failures in Nectar

A while ago, there were a few support tickets about instance snapshots not working. Looking into them, we could see that the snapshots were created, but uploads to our storage were failing randomly.

A little backstory - Nectar uses Swift as a backend to Glance. We run a ‘national’ swift cluster consisting of swift storage nodes from all over Australia. When an instance is snapshotted, an image of the disk is created and uploaded into Swift.

Swift handles large objects (like images) by chunking them into pieces and

uploading each chunk as a separate object 1. Each object/chunk is uploaded to

3 servers for reliability. So a simplified flow looks like Nova -> Glance ->

Swift proxy server -> Swift object servers (3)

In detail, we saw that random chunks will fail, and when it happened Swift will rollback the whole upload. This is a HTTP PUT call that failed:

p1-rcs-qh2 proxy-server <14>2018-01-09T04:30:02.064113+11:00 p1-rcs-qh2

proxy-server: XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX 127.0.0.1 08/Jan/2018/17/30/02 PUT

/v1/AUTH_3/images/910d0b24-cc93-4330-8320-edc68fa26692-00019 HTTP/1.0 500 -

python-swiftclient-3.1.0 gAAAAABaU6md7mxb... 204800000 125 -

txcd773598661349caa17b1-005a53aa87 - 18.6902 - - 1515432583.373755932

1515432602.063934088 0

As you can see from the log, this particular image failed at chunk 00019.

Another interesting log message was:

2018-01-16T15:51:57.930405+11:00 p1-rcs-qh2 proxy-server: Object servers

returned 2 mismatched etags (txn: txe0bd4b7f34dc46928014b-005a5d84d4)

(client_ip: XXX.XXX.XXX.XXX)

Reading the swift code, we found that Swift object servers checksums the object after writing it to disk and returns the checksum to the Swift proxy server. The proxy server compares checksums from each of the 3 object servers to make sure all of them match, before returning a HTTP 200 to the client doing the PUT.

This leads us to believe that one or more copies of the object were being corrupted when they were being uploaded to their object servers for storage. The failures was seemingly random and affected less than 0.1% of our total Swift calls. This made it hard to replicate and track down; there was no clear patterns.

- Failed snapshots vary in sizes

- Snapshots failed at varying chunks. It can fail at chunk 19, or chunk 59. Chunk sizes are the same.

- Instances vary in different availability zones

- Instances that failed once could be OK with the next snapshot, or they could be successful only after multiple retries

As this issue only affected a small portion of our requests, and mostly fixed itself after a few retries, we did not pay much attention to it at first. Until one day, we got an image which consistently fails, even after many retries. Now that got us intrigued and we dug deeper…

We compiled a list of all the historical failures and tried to see if there was

a pattern to them. We tried to find out which servers were involved with a

failed object. Swift deterministically assigns an object to a set of object

servers by hashing the object name 2. Using swift-get-nodes, we can find out

what servers are assigned to hold an object

swift-get-nodes [-a] <ring.gz> <account> [<container> [<object>]]

ring.gzis the ring file, which holds information on number of devices, servers, how copies should be distributed, etc.account,container,objectmakes up the name of the object; and you can grab them from the HTTP URL.

For example, this is a HTTP call that was failing:

PUT /v1/AUTH_3/images/910d0b24-cc93-4330-8320-edc68fa26692-00019

AUTH_3is the accountimagesis the container910d0b24-cc93-4330-8320-edc68fa26692-00019is the object.

When we did this, a pattern was obvious immediately - all the failed objects always had an IP from a particular site (let’s call it site S).

We also looked at the image that was failing. With the permission of the image

owner, we got a copy of the image. We wanted to replicate the failure, so we

chunked it like how Swift would, by using split. We also needed to upload each

chunk to site S, so we had to choose a file name allow us to do so. This just

meant running swift-get-nodes with random filenames until we got what wanted.

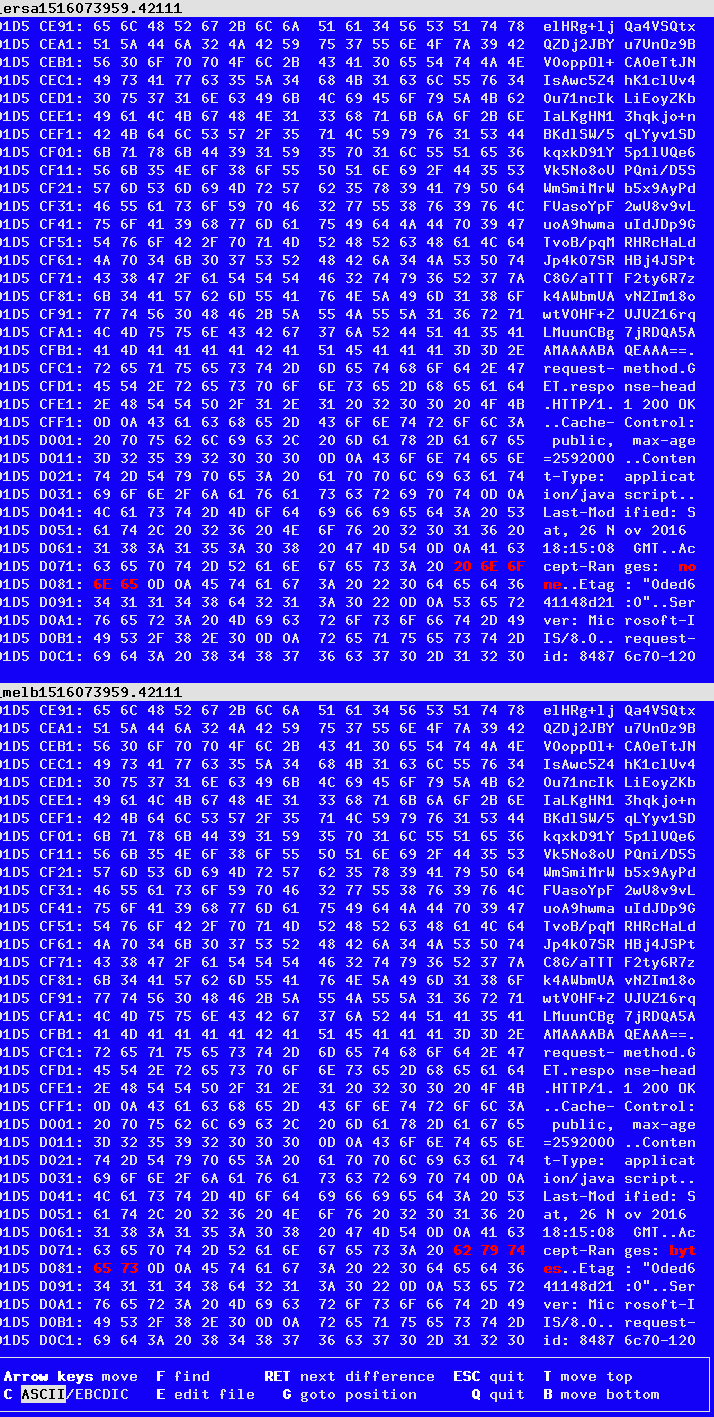

Success! By that I mean we had a failure. A closer look each of the 3 copies of the data did show that they were different. Diffing them, it was immediately obvious.

Fuzzing that image, we managed to reduce it to the following contents that will throw an error. Below is a comparision of the same object on 3 servers

root@p2-rcs-qh2:/tmp# curl

"http://118.138.XXX.XXX:6000/sde1/257086/AUTH_f42f9588576c43969760d81384b83b1f/jake-zzz/a"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Accept-Ranges: bytes

root@p2-rcs-qh2:/tmp# curl

"http://130.220.XXX.XXX:6000/sdg/257086/AUTH_f42f9588576c43969760d81384b83b1f/jake-zzz/a"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Accept-Ranges: none

root@p2-rcs-qh2:/tmp# curl

"http://115.146.XXX.XXX:6000/nlsas11/257086/AUTH_f42f9588576c43969760d81384b83b1f/jake-zzz/a"

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Accept-Ranges: bytes

Turns out that the site had an F5 appliance on the network that wrongly messed with the contents of a HTTP stream, instead of just the HTTP headers. They excluded Nectar traffic and everything worked properly after.

This is one of the reason why Nectar wants sites to set up their cloud outside of enterprise firewalls. Even with trusted brands, they can be misconfigured or have subtle bugs. This particular misbehaving F5 wasted a number of operator hours which could have gone into building better things.

Lots of thanks to the great colleagues at Nectar who were involved in this debugging this issue, especially Matt Armsby from University of Tasmania.